In 2016, Will Smith spoke candidly about race relations during an interview with Stephen Colbert on The Late Show. “When I hear people say it’s worse than it’s ever been I disagree completely,” Smith said. “Racism isn’t getting worse, it’s getting filmed.” Those words couldn’t be more accurate four years later in 2020 after we’ve witnessed false and potentially fatal 911 calls on African Americans and cold-blooded murders, some filmed and some not.

This is not new. This is not normal. Spanning from about six years ago when people (and kids) like Tamir Rice, Eric Garner, Trayvon Martin, Sandra Bland, Alton Sterling, Philando Castile, and too many others were mercilessly murdered, I, like many others, felt like I was going crazy. Some family and friends felt I was becoming obsessed with trying to figure out how and why a country that supposedly isn’t racist continues to sanction the disproportionate murder and incarceration rates of black people. I needed answers and some sort of rationality as to how and why a supposed “Christian” nation that touts liberty and justice for all is consistently marked by oppression and injustice for some. I read books. I studied beyond the surface-level whitewashed grade school history I received. I listened to podcasts. I wrote articles. All were attempts to grieve and make sense of the assault on black and brown bodies that looked like mine and my friends, and to hopefully educate and liberate my friends and family who failed to see the interwoven effects of white supremacy laced throughout our culture.

It did not work. So I quieted myself and suppressed the angst and hope I had for a better country. A country where nobody had to feel the anxiousness that arises when a police officer drives up behind, beside, or in front of them. An anxiousness that requires me to make sure I have my wallet on me for identification purposes to go on a walk in my neighborhood, just in case I get questioned on suspicion—just to prove I am a person. An anxiousness that drives me to not feel fully free to do my job as I hear my white students getting into a car yelling “nigger nigger nigger” to each other as a joke to put down each other. An anxiousness that makes me wonder how my students truly feel about me as their teacher—as a black man—as I see them walk into class with their “Make America Great Again” t-shirts on and their “Trump 2020” flags flying high in the back of their pickup trucks. An anxiousness felt every time I walk into work knowing my coworkers think Colin Kaepernick is a “dumbass” because he honorably and quietly took a knee during the national anthem to protest state-sanctioned murder of minorities. An anxiousness that sees the way “Reopen America” protestors, armed with AR-15s, yell in the face of police officers inside capitol buildings—because they want haircuts—are met with calm and patience, while I’m left wondering why Black Lives Matter protestors are met with tear gas and rubber bullets.

I suppressed all of this and went about my business, numbing myself to systemic and individual racism and the pervasive ignorance of my neighbors that allowed them to profit off of the comforts of white supremacy. I ignored subversively veiled racist comments from my coworkers. I felt bad for, but wouldn’t allow myself to emotionally engage in Christian Hip Hop artist KB’s encounter with the police in his own driveway. Even as of recently, I suppressed my raw emotions about Ahmad Arbury and Breonna Taylor on a podcast episode in hopes not to offend any of my neighbors, having to defend why it’s wrong to kill people without consequences. But suppression and unforgiveness only give birth to bitterness.

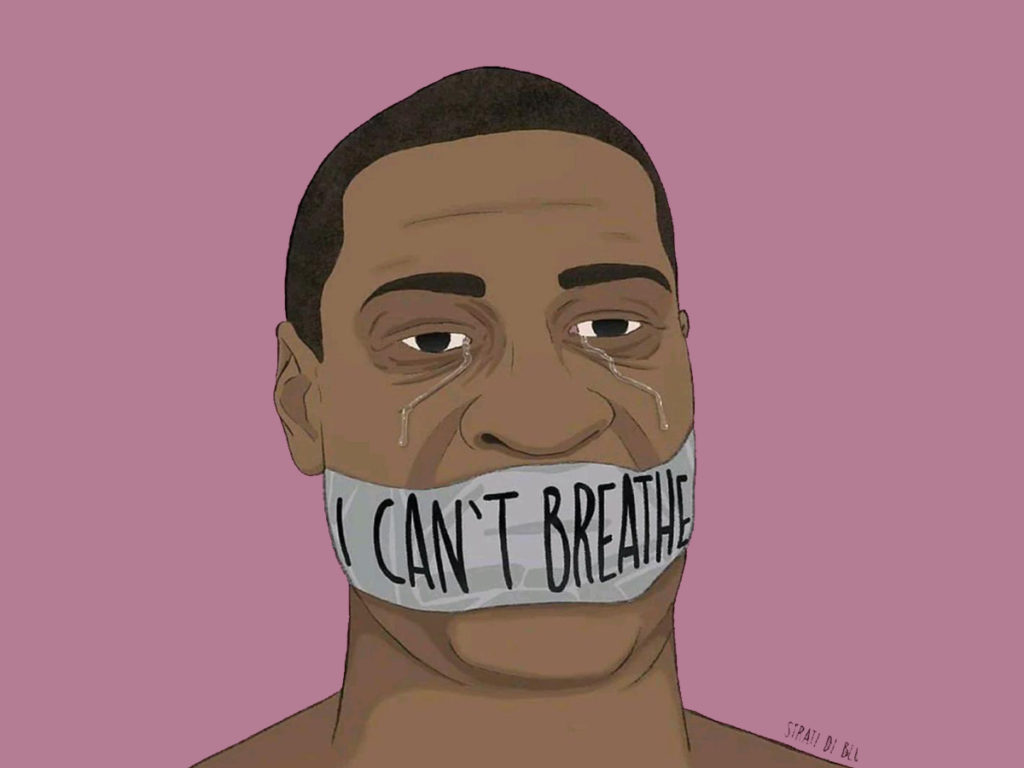

So when Midland police officers drew their guns on Mr. Anders in his front yard for rolling through a stop sign, I could understand his and his neighbors frenzied panic, but I stopped myself from taking a moment to sympathize—even though the chaos caused his 90-year-old grandmother to collapse during the event. And when Amy Cooper was caught on film calling the police, pretending to be threatened by “an African American male,” I was not surprised and I tried to suppress some more. And when George Floyd was mercilessly and nonchalantly crushed by Minneapolis police officers, I tried stuffing my feelings deeper into my soul. It all only gave way to more bitterness.

My bitterness turned to frustration and anger as now there seems to be more public outrage about Floyd’s murder than most of the other previous murders mentioned here. Why now? Why do so many more seem to care now? Is it because you had to listen to a man’s last words? Is it because you had to witness his eyes fade from life to death before your eyes? What about the murders we didn’t see, or maybe even the ones we did see but allowed ourselves to be removed from their humanity?

George Floyd’s murder was premeditated. Floyd’s is not an isolated incident. Similar circumstances have happened for centuries. Laws have been put in place to protect the practice of killing black people. The facts were there. The articles were there. The books and documentaries were there. Other documented video evidence was also there before all of this. There’s much that we knew. We knew race as we define it today is a scientific myth. But we also know (whether we ignore it or not) that racism, however, is a social construct that has financial, egotistical, and hierarchical benefits.

Though we know all these things, nothing substantive about changing policing practices, stand-your-ground, open-carry, and citizen’s arrest laws have substantiated. Instead, the infuriating tasks of trying to convince people how these things are tied together and are negatively affecting the livelihood of minorities have been largely ignored. Now politicians, feeling the shifting breeze of the public outcry of Mr. Floyd’s murder towards a desire for justice, see an opportunity to capitalize on the fears and anger of the general population. (It is also a moment to shift the focus from their mishandling of the coronavirus pandemic.)

As a result, maybe one officer will be charged with murder, as the sacrifical lamb if you wlll. Maybe all three will be charged. Perhaps even all four policemen—including officer Thao who watched and protected the other officers that sat on Mr. Floyd as he called out for his mother and his kids with his final breaths, as if he was a beast to be tamed instead of a cherished child of God—will be charged. Most of us will be disappointed, but not surprised if some or none will be judged guilty in a court of law. We’ve seen this story too many times. But family and friends who’ve called me obsessed in the past assure me that will not be the case this time. But again, why now?

Even if they are charged and judged guilty, my cynicism informs my reality that nothing will change. There will be another George Floyd, unfortunately. Unless God convicts our country’s conscience enough to rid ourselves of white supremacy and to instead see all of humanity as our neighbors as Jesus taught, this will not be the last time we hear of or witness another state-sanctioned murder. Regardless, the onus is not on people without power to fix these racial problems. Racism isn’t going anywhere. As author Toni Morrison said, “Racism will disappear when it’s no longer profitable, and no longer psychologically useful. And when that happens, it’ll be gone. But at the moment, people make a lot of money off of it.” But again—though there is truth to this all—this is but a more intelligent expression of my cynicism. Cynical statements are the small whiffs of bitterness that leak from the suppression of disappointment.

After watching former NBA basketball player Stephen Jackson speak about his friend George Floyd, the suppression that dammed my emotions for the past year or so finally cracked and eventually ruptured. My eyes flooded with tears and my heart burst open with feeling again. George Floyd was not just another statistic. He was a God-fearing man. He baptized people, Jackson said. Hip hop artists and community activists Reconcile and Corey Paul talked about his efforts to help pull young men in broken neighborhoods up and out of despair in exchange for hope that extended beyond their situations improving.

So in that light, I pray because of George Floyd’s humanity. I am encouraged by his life. The waves of emotion will calm. Anger will simmer. But my hope in Jesus remains. These unjust murders are not new. And as my friend Joseph Solomon says, they are not normal. Yet, “Some still need to see a body with holes in it, just so they can believe it’s true.”

Hip hop artist Lecrae offered wisdom on his Instagram story for these situations that leave me and many others feeling overwhelmed. He said the lie we tend to believe is that God isn’t big enough and Jesus not more powerful than these circumstances. “Death and evil have been defeated,” Lecrae said, “and even though we’re experiencing the last kicking and screaming of it, it’s been defeated and we can hope in the work of Jesus.”

Similarly, Augustine of Hippo offers timeless wisdom as well: “Hope has two beautiful daughters; their names are Anger and Courage. Anger at the way things are, and Courage to see that they do not remain as they are.” So if we really care about an unjust murder, we must honestly ask ourselves what we are willing to sacrifice to ensure this is no longer a regular practice, because as Will Smith said, “Racism isn’t getting worse, it’s getting filmed.” And now that we’ve seen a man’s life stolen from him, seemingly more clear than before, may our anger and sadness fuel the lamps of our courage to light our present darkness.

Author’s Bio – Timothy Thomas:

Timothy Thomas is a full-time public school teacher and coach. He is also a part-time staff writer for Christ and Pop Culture Magazine. He lives in Fort Worth, Texas with his wife, Angela. He is devoted to encouraging, informing, and challenging the culture at-large.

His socials for twitter and Instagram: timothyt_t